Flight Officer Philip F. Walters

Flight Officer Philip F. Walters

Phil Walters (aka “Ted Tappett”) was a famed automobile race car driver before and after World War II.

Lesser known about him was his military service during WWII. As a glider pilot, among other campaigns, he participated in the Invasion of Sicily, Normandy (D-Day +1), and the ill-fated Operation Market Garden. Landing in Holland on September 18, 1944, he was wounded, taken prisoner, and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp. He eventually returned to racing.

Almost a quarter century after his passing in 2000, a meticulous hand-written presentation to an aviation association was found among his papers. This abbreviated version jumps directly to Operation Market Garden and skips his remarks about glider training, the North Africa Campaign, the Invasion of Sicily, and D-Day +1. The story is rounded out by some remarkable newspaper clippings and other artifacts (kept in scrapbooks by his parents.) --Rick Grimes (Son-in-Law)

Lesser known about him was his military service during WWII. As a glider pilot, among other campaigns, he participated in the Invasion of Sicily, Normandy (D-Day +1), and the ill-fated Operation Market Garden. Landing in Holland on September 18, 1944, he was wounded, taken prisoner, and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp. He eventually returned to racing.

Almost a quarter century after his passing in 2000, a meticulous hand-written presentation to an aviation association was found among his papers. This abbreviated version jumps directly to Operation Market Garden and skips his remarks about glider training, the North Africa Campaign, the Invasion of Sicily, and D-Day +1. The story is rounded out by some remarkable newspaper clippings and other artifacts (kept in scrapbooks by his parents.) --Rick Grimes (Son-in-Law)

Transcript of Phil Walters' presentation to the Citrus Aviation Association:

OPERATION MARKET GARDEN

"By mid-1944 a little over two months since the landings at Normandy, the Allied troops had forced the Germans to retreat across France and Belgium. The German retreat was very disorganized. It seemed to be every man for himself back to the Fatherland.

"To take advantage of the disarray, General "Monty" Montgomery sold his boss (General Dwight Eisenhower) on an operation for mid- September that he said would end the war before Christmas! However, because of the scarcity of pilots and aircraft, the invasion had to take place over three successive days: September 17, 18, and 19, 1944."

[Unbeknowst to anyone, the plan for Operation Market Garden had been compromised by a Dutch double agent on September 15. Thus, the Germans were prepared and lying in wait. RG]

C-47's towing Waco gliders over Holland during Market Garden

C-47's towing Waco gliders over Holland during Market Garden

LANDINGS IN HOLLAND

"I was a part of the second day fleet (September 18, 1944).

"My CG4A was loaded with a trailer full of ammunition, a machine gun, and 13 airborne troops.

"The allied fighters prevented any problems with German fighters but we were subject to flak from the ground, some of which hit me in the thighs, buttocks, and back, about 20 minutes from the landing zone.

"I started to feel normal again after about the first few minutes of pain but nothing that interfered with my ability to keep flying. This was a good thing, since I didn’t have a co-pilot! We were hauling every last pound possible and had substituted a co-pilot for extra supplies and ammunition."

"I was a part of the second day fleet (September 18, 1944).

"My CG4A was loaded with a trailer full of ammunition, a machine gun, and 13 airborne troops.

"The allied fighters prevented any problems with German fighters but we were subject to flak from the ground, some of which hit me in the thighs, buttocks, and back, about 20 minutes from the landing zone.

"I started to feel normal again after about the first few minutes of pain but nothing that interfered with my ability to keep flying. This was a good thing, since I didn’t have a co-pilot! We were hauling every last pound possible and had substituted a co-pilot for extra supplies and ammunition."

"As we approached the field we were to land in, I was struck with fear to see several German Tiger tanks nearby to the east and considerable German infantry surrounding the field. In each corner of the field, there were machine guns shooting up at us with tracer bullets.

"I immediately made an abrupt diving turn to the west, where about a mile away there was a slight hill. If we could make it to the other side of the hill, we would be out of sight and range of the machine guns. In the interest of speed, I dove sharply until we reached the red line on the speedo and coasted at treetop level to the area I was hoping to land in. The good Lord must’ve figured we were worthy of saving as we touched down just inside the field.

"I immediately made an abrupt diving turn to the west, where about a mile away there was a slight hill. If we could make it to the other side of the hill, we would be out of sight and range of the machine guns. In the interest of speed, I dove sharply until we reached the red line on the speedo and coasted at treetop level to the area I was hoping to land in. The good Lord must’ve figured we were worthy of saving as we touched down just inside the field.

"As we were landing, the remaining problem was avoiding several horses that were galloping around as if they thought we were crazy. Again, we were lucky. We missed the horses and I steered to a stop next to a ditch that was deep enough to protect us if the Germans started shooting at us.

"We immediately started unloading the trailer but before we got the trailer out, we came under heavy machine gun fire. Before their aim was upon us, we were all in the ditch. Bullets galore screamed by us just above ground level, parting the dirt just above our heads. We set up a machine gun and exchanged fire for a while, but they started bringing in bigger stuff—mortars and 88’s. After several minutes, a hand grenade exploded right next to me. Unfortunately, the first I knew of it was after it exploded.

"We immediately started unloading the trailer but before we got the trailer out, we came under heavy machine gun fire. Before their aim was upon us, we were all in the ditch. Bullets galore screamed by us just above ground level, parting the dirt just above our heads. We set up a machine gun and exchanged fire for a while, but they started bringing in bigger stuff—mortars and 88’s. After several minutes, a hand grenade exploded right next to me. Unfortunately, the first I knew of it was after it exploded.

Three Waco gliders in various positions landing or readying to land in Holland.

Three Waco gliders in various positions landing or readying to land in Holland.

"I sustained shrapnel in the right kidney and lung. I passed out but when I came to, there was a German sergeant standing over me with his pistol pointed at my head. He said in pretty good English: “Now let’s be gentlemen. Your weapons have been removed and you will now receive medical attention.”

"(To this day, I don’t know what happened to the other airborne troops that I brought in on the glider.)

"While waiting my turn at a German first aid tent, I passed out again. The next thing I knew, I was on a truck with a number of other seriously wounded. (By the way, it has always bothered me that the truck was a Ford!) We were taken to a large Navy hospital about twenty miles into Germany at a town called Cleves.

"The doctor at the hospital said 'I must remove your right kidney.' I asked 'Can’t you just fix it?' He responded 'No. Removal is essential to life.' "

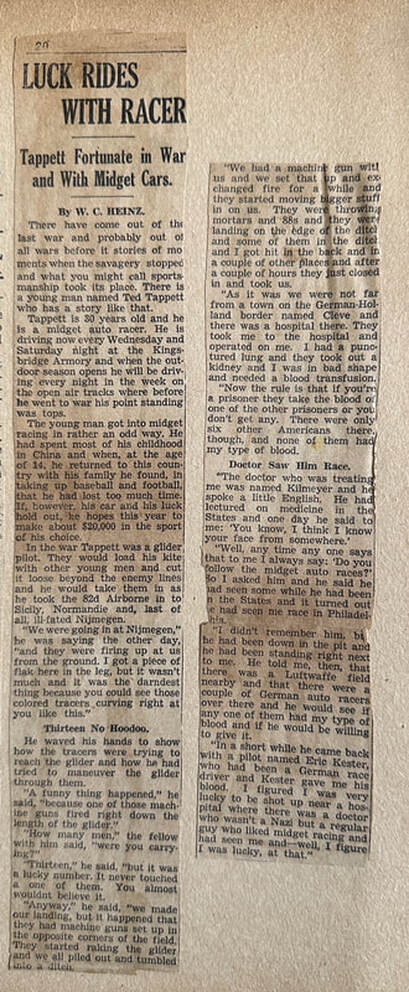

"An hour after arriving I was on the operating table. I had a punctured lung, and they took out a kidney and I was in bad shape and needed a blood transfusion. Now the rule is that if you are a prisoner, they take the blood of one of the other prisoners or you don't get any. However, there were only six other Americans there, and none of them had my type of blood.

"The doctor who was treating me was named Kilmeyer and he spoke a little English. He had lectured on medicine in the states and one day he said to me 'You know, I think I know your face from somewhere.' Well, any time any one says that to me I always say: 'Do you follow the midget auto races?' So I asked him and he said had seen some while he had been in the States and it turned out he had seen me race in Philadelphia. I didn't remember him, but he had been down in the pit and he had been standing right next to me. He told me that there was a Luftwaffe field nearby and that there were a couple of German auto racers over there and he would see if any one of them had my type of blood and if they would be willing to give it to me.

"In a short while he came back with a pilot named Eric Kester who had been a German race driver and Kester gave me his blood. I figured I was very lucky to be shot up near a hospital where there was a doctor who wasn't a Nazi but a regular guy who liked midget racing and had seen me and--well I figured I was lucky, at that."

"(To this day, I don’t know what happened to the other airborne troops that I brought in on the glider.)

"While waiting my turn at a German first aid tent, I passed out again. The next thing I knew, I was on a truck with a number of other seriously wounded. (By the way, it has always bothered me that the truck was a Ford!) We were taken to a large Navy hospital about twenty miles into Germany at a town called Cleves.

"The doctor at the hospital said 'I must remove your right kidney.' I asked 'Can’t you just fix it?' He responded 'No. Removal is essential to life.' "

"An hour after arriving I was on the operating table. I had a punctured lung, and they took out a kidney and I was in bad shape and needed a blood transfusion. Now the rule is that if you are a prisoner, they take the blood of one of the other prisoners or you don't get any. However, there were only six other Americans there, and none of them had my type of blood.

"The doctor who was treating me was named Kilmeyer and he spoke a little English. He had lectured on medicine in the states and one day he said to me 'You know, I think I know your face from somewhere.' Well, any time any one says that to me I always say: 'Do you follow the midget auto races?' So I asked him and he said had seen some while he had been in the States and it turned out he had seen me race in Philadelphia. I didn't remember him, but he had been down in the pit and he had been standing right next to me. He told me that there was a Luftwaffe field nearby and that there were a couple of German auto racers over there and he would see if any one of them had my type of blood and if they would be willing to give it to me.

"In a short while he came back with a pilot named Eric Kester who had been a German race driver and Kester gave me his blood. I figured I was very lucky to be shot up near a hospital where there was a doctor who wasn't a Nazi but a regular guy who liked midget racing and had seen me and--well I figured I was lucky, at that."

[*SEE ARTICLE. "LUCK RIDES WITH RACER." After the war, Phil was interviewed by a newspaper reporter about how he survived and the story of getting blood from a Luftwaffe pilot is included above.]

"I spent about 10 days recovering at the hospital during which time I developed pneumonia. This resulted in the permanent loss of the use of my right lung. The Germans at that time had no penicillin—so I was cured the old-fashioned way--- without antibiotics...

"One day a doctor came into the ward where a group of paratroopers and I were recuperating. He said, 'Tomorrow morning, you will be transported to a safer hospital inland because it appears the battle may overrun this area, and if that should happen before we can move you, please tell your people the truth that you were well taken care of.'

"Unfortunately, the battle didn’t overrun the hospital that night, so on October 5th, the wounded were put in a truck (this time a Mercedes) and we started for Wesel, Germany. (Incidentally, the Allies didn't actually overrun the area until about 6 months later!)

"A German soldier sat on the front fender of the truck, looking for Allied fighters that would strafe anything that moved. Sure enough, a P-51 Mustang spotted us. The driver, the lookout soldier, and the ambulatory patients quickly headed for the nearest ditch. However, one other patient and I were not ambulatory and therefore, well, we had choice seats to watch the show!

"The truck was hit, but miraculously, the two of us who remained in the truck were not hit and the truck remained in running order. I’ll never know why the P-51 pilot made only one pass--perhaps it was the red crosses crudely painted on the doors.

("One of my good friends was a P-51 pilot named John Fitch and, after the war, I accused him of shooting at me. I told him I recognized his face—joking, of course.)" [John Fitch and Phil Walters met after the war and became friends and co-drivers for Cunningham.]

"I spent about 10 days recovering at the hospital during which time I developed pneumonia. This resulted in the permanent loss of the use of my right lung. The Germans at that time had no penicillin—so I was cured the old-fashioned way--- without antibiotics...

"One day a doctor came into the ward where a group of paratroopers and I were recuperating. He said, 'Tomorrow morning, you will be transported to a safer hospital inland because it appears the battle may overrun this area, and if that should happen before we can move you, please tell your people the truth that you were well taken care of.'

"Unfortunately, the battle didn’t overrun the hospital that night, so on October 5th, the wounded were put in a truck (this time a Mercedes) and we started for Wesel, Germany. (Incidentally, the Allies didn't actually overrun the area until about 6 months later!)

"A German soldier sat on the front fender of the truck, looking for Allied fighters that would strafe anything that moved. Sure enough, a P-51 Mustang spotted us. The driver, the lookout soldier, and the ambulatory patients quickly headed for the nearest ditch. However, one other patient and I were not ambulatory and therefore, well, we had choice seats to watch the show!

"The truck was hit, but miraculously, the two of us who remained in the truck were not hit and the truck remained in running order. I’ll never know why the P-51 pilot made only one pass--perhaps it was the red crosses crudely painted on the doors.

("One of my good friends was a P-51 pilot named John Fitch and, after the war, I accused him of shooting at me. I told him I recognized his face—joking, of course.)" [John Fitch and Phil Walters met after the war and became friends and co-drivers for Cunningham.]

"Late in the afternoon, we arrived at the city of Wesel, a fairly large city in Northwest Germany. We were put up on the floor at a school gymnasium for the night. We were not fed anything but a military doctor came around about 9 PM and offered each one of us an injection which he touted 'will make you comfortable for the night.' I rejected the offer but later---too late—I wished I hadn’t! What a night that was on a hardwood floor! (And, about midnight, I could feel that I had a pretty high temperature.)

"The next day, October 6, we arrived at Gelsenkirchen at the head of the Ruhr River where we were delivered to a hospital—a Catholic hospital (Saint Marien) where the nurses were nuns. We couldn’t have gotten better nursing care. The doctors were older men--too old to be in the military. They showed no sign of being 'Nazified' and generally treated us well.

"The food at the hospital was good if not monotonous. Breakfast consisted of ersatz coffee without sugar or milk and black bread. (On Christmas day, we also got a hard-boiled egg.) Lunch consisted of soup and again, black bread. Usually, the soup was potato soup. For dinner, we had boiled potatoes and more black bread. (The black bread had the same effect as Metamucil!) It was my understanding from the nuns that with the exception of a few high-ranking officers and a few of the very sick, this was the menu for everyone.

"The bad part about being in the hospital was its location near the Ruhr Valley--a German industrial center. Consequently, the area was bombed almost daily--the Americans by day and the English by night.

"The red crosses painted on the roof did little to relieve my anxiety: At night and in certain weather conditions, the red crosses couldn’t be seen from the air. Anyway, the hospital never received a direct hit. The nearest was a bomb that landed on the front lawn about 100 feet from the building and just below the windows of our ward.

"The bomb that landed in the front yard was directly below our room’s windows. It’s interesting to note that the force of the bomb blew the glass out of the windows and across the room and slammed into the opposite wall right over my head, without one bit of glass touching me.

"The bombs that landed further away also broke windows but, with less force. The broken glass would just fall to the floor below the windows.

"During air raids, ambulatory patients were allowed to go into the cellar. Non-ambulatory patients just stayed in their beds and...became quite religious...

"The next day, October 6, we arrived at Gelsenkirchen at the head of the Ruhr River where we were delivered to a hospital—a Catholic hospital (Saint Marien) where the nurses were nuns. We couldn’t have gotten better nursing care. The doctors were older men--too old to be in the military. They showed no sign of being 'Nazified' and generally treated us well.

"The food at the hospital was good if not monotonous. Breakfast consisted of ersatz coffee without sugar or milk and black bread. (On Christmas day, we also got a hard-boiled egg.) Lunch consisted of soup and again, black bread. Usually, the soup was potato soup. For dinner, we had boiled potatoes and more black bread. (The black bread had the same effect as Metamucil!) It was my understanding from the nuns that with the exception of a few high-ranking officers and a few of the very sick, this was the menu for everyone.

"The bad part about being in the hospital was its location near the Ruhr Valley--a German industrial center. Consequently, the area was bombed almost daily--the Americans by day and the English by night.

"The red crosses painted on the roof did little to relieve my anxiety: At night and in certain weather conditions, the red crosses couldn’t be seen from the air. Anyway, the hospital never received a direct hit. The nearest was a bomb that landed on the front lawn about 100 feet from the building and just below the windows of our ward.

"The bomb that landed in the front yard was directly below our room’s windows. It’s interesting to note that the force of the bomb blew the glass out of the windows and across the room and slammed into the opposite wall right over my head, without one bit of glass touching me.

"The bombs that landed further away also broke windows but, with less force. The broken glass would just fall to the floor below the windows.

"During air raids, ambulatory patients were allowed to go into the cellar. Non-ambulatory patients just stayed in their beds and...became quite religious...

Saint Marien Hospital in Gelsenkirchen (today)

Saint Marien Hospital in Gelsenkirchen (today)

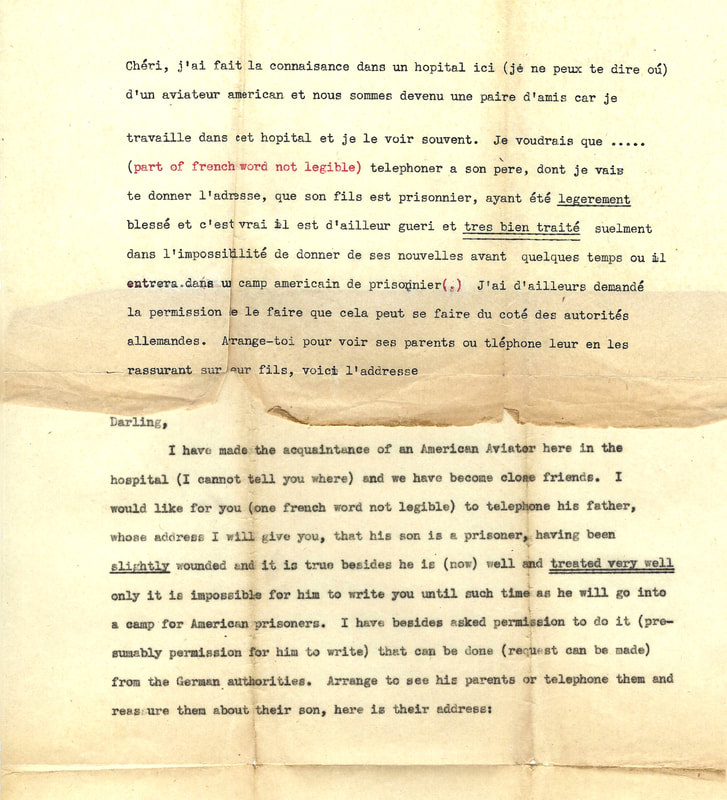

"The bomb-damaged windows were repaired by a work group of about eight French prisoners with a German guard in charge and one day one of the French prisoners, Henri, came into the ward to replace the windows and asked 'Anyone here from New York?' "

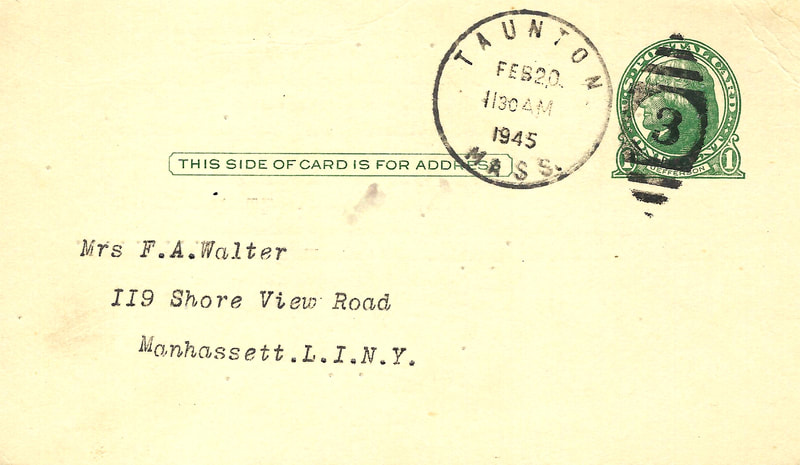

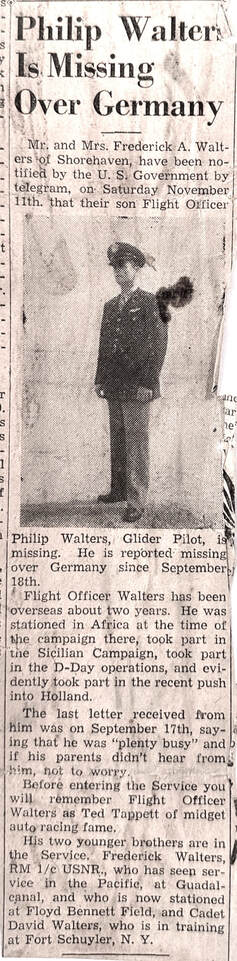

"It turned out, Henri had been a steward on the French liner Normandie and had a girlfriend named Lulu who worked in a French restaurant in Kew Gardens, New York. He reminded me that until prisoners are registered in a POW camp, their families are not notified. I was captured on September 18 and I learned later that my parents were not notified that I was even Missing in Action until November 11. My parents didn’t know if I was dead or alive.

"Henri said 'I can write my girlfriend and have her contact your family and tell them you’re okay.' ” He did.

"It turned out, Henri had been a steward on the French liner Normandie and had a girlfriend named Lulu who worked in a French restaurant in Kew Gardens, New York. He reminded me that until prisoners are registered in a POW camp, their families are not notified. I was captured on September 18 and I learned later that my parents were not notified that I was even Missing in Action until November 11. My parents didn’t know if I was dead or alive.

"Henri said 'I can write my girlfriend and have her contact your family and tell them you’re okay.' ” He did.

_________________________

"Subsequently, Lulu telephoned my folks who learned for the first time that I was alive. I’m sure you realize the relief they must have felt. But little did they know the risks I would still encounter before getting home."

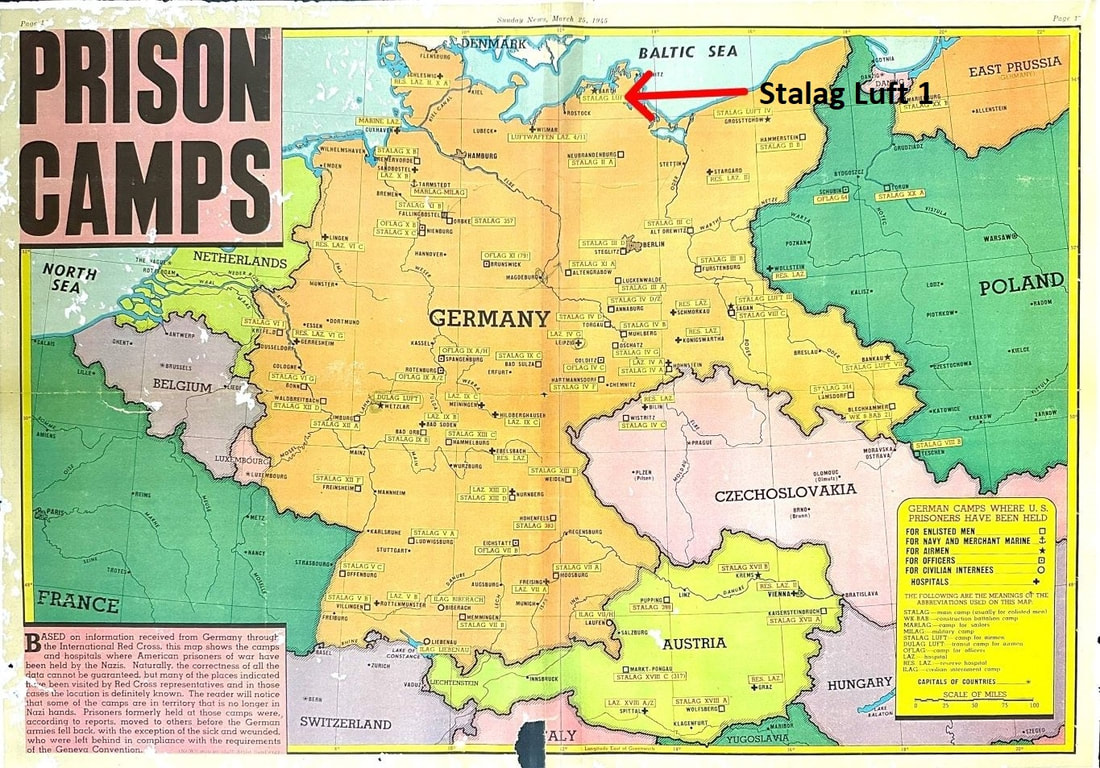

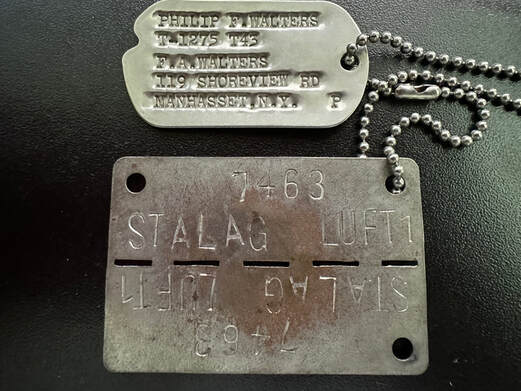

STALAG LUFT 1--GERMAN POW CAMP FOR AVIATORS

[Phil was transferred from the Saint Marien hospital to a prison camp near the Baltic Sea about mid-February, 1945. He had been in German hands since September 18, 1944.]

"Subsequently, Lulu telephoned my folks who learned for the first time that I was alive. I’m sure you realize the relief they must have felt. But little did they know the risks I would still encounter before getting home."

STALAG LUFT 1--GERMAN POW CAMP FOR AVIATORS

[Phil was transferred from the Saint Marien hospital to a prison camp near the Baltic Sea about mid-February, 1945. He had been in German hands since September 18, 1944.]

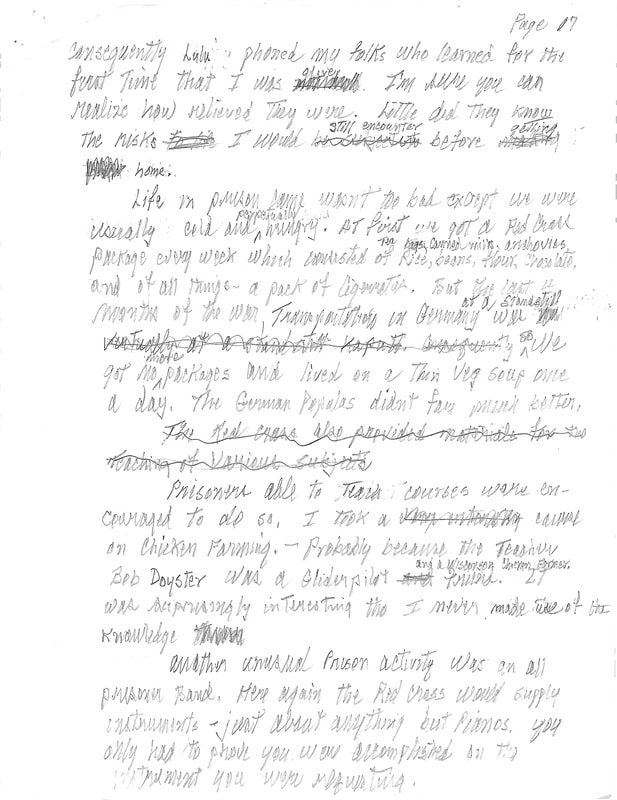

"Life in prison camp wasn’t too bad except we were usually cold and perpetually hungry. At first we got a Red Cross package every week which consisted of rice, beans, flour, chocolate, tea bags, canned milk, and anchovies—and, of all things—a pack of cigarettes. But during the last four months of the war, transportation in Germany was at a standstill. We got no more packages and lived on a thin vegetable soup once a day. The German people didn’t fare much better.

"Prisoners able to teach courses were encouraged to do so. I took a course on chicken farming-- probably because the teacher (Bob Doyster) was a glider pilot and a Wisconsin chicken farmer. The course was surprisingly interesting but I never made use of the knowledge."

________________________

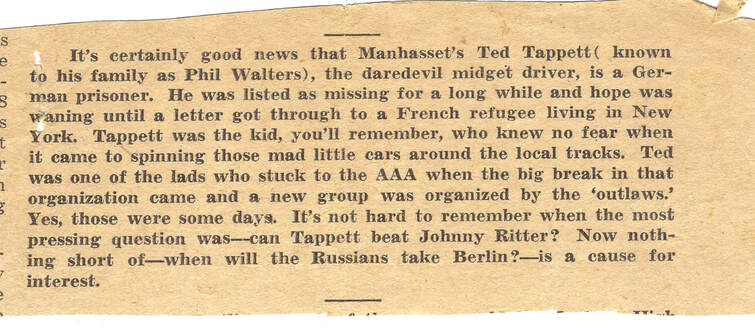

[Sometime after Phil’s parents heard from Lulu, they heard officially from the U.S. government. And soon thereafter it was known by his friends and the press that he was alive and a POW. A friend of Phil’s father sent him a clipping from the Daily News:]

"Prisoners able to teach courses were encouraged to do so. I took a course on chicken farming-- probably because the teacher (Bob Doyster) was a glider pilot and a Wisconsin chicken farmer. The course was surprisingly interesting but I never made use of the knowledge."

________________________

[Sometime after Phil’s parents heard from Lulu, they heard officially from the U.S. government. And soon thereafter it was known by his friends and the press that he was alive and a POW. A friend of Phil’s father sent him a clipping from the Daily News:]

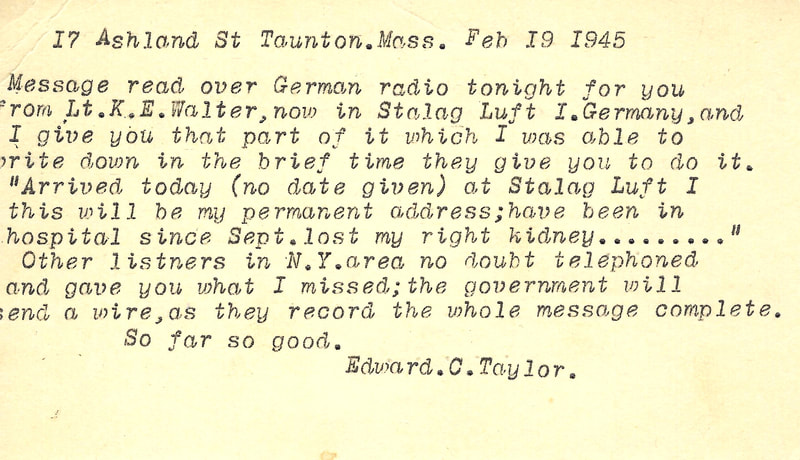

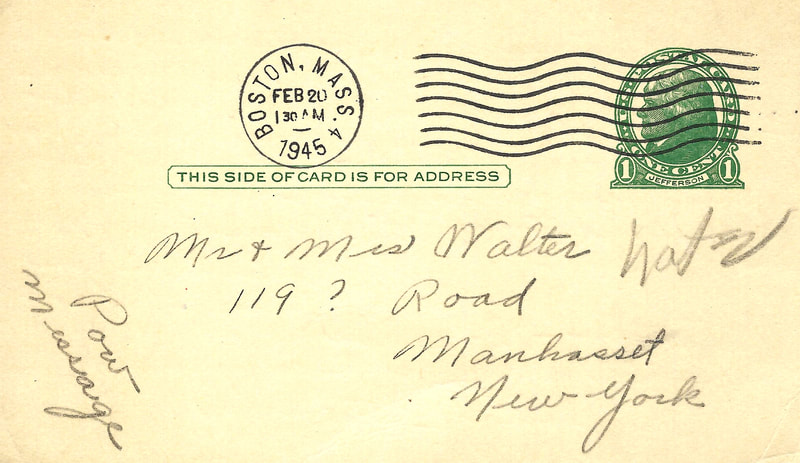

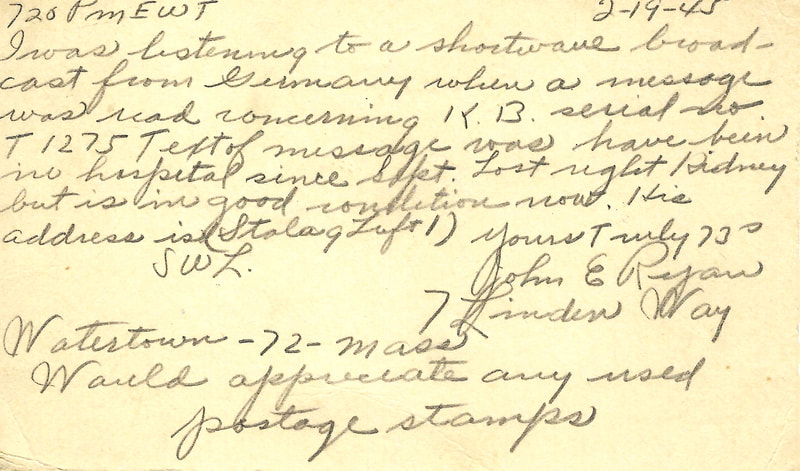

[On the day he arrived at Stalag Luft 1, Phil had an opportunity (or was forced?) to broadcast live to the U.S. --no doubt a propaganda effort--on a German shortwave radio. Soon thereafter, Phil's parents received at least two post cards from people who had heard the broadcast.]

______________________

"About the time of Hitler’s death, our camp was liberated by the Russians (May 1, 1945), The guards had left, and the Russians came galloping in on horses, accompanied by an assortment of vehicles, including jeeps. They asked how they could help us. We said, “Food. We’re all starving.” Next thing you know, the Russians are herding liberated chickens and pigs into the camp. Man, did we all get sick.

"I won’t go any further about the POW camp as I’m sure a number of movies have covered it well."

GOING HOME

"The day after Germany’s unconditional surrender was signed (May 7, 1945), a number of B-17’s landed at an adjacent field where there had been a factory that produced the German jets—the first to provide them. In conjunction with the plant there was one runway I estimated to be at least 6,000 feet long. ["Operation Revival: Rescue from Stalag Luft 1."]

"Since I was listed as an ambulatory patient with a pulmonary problem, I went out on one of the first B-17’s along with a few from the Camp Hospital. We wound up in a large hospital near Paris where they gave us a physical and any needed treatment. And, they scheduled our trip back to the states.

"While in the hospital, I noticed at the foot of each POW’s bed a large envelope containing his records. There also was a 12-inch by one inch strip of either blue or orange paper. I asked the nurse what the color stripes were for and she said: 'If it’s blue, you are going home by air the day after tomorrow. And if it’s orange, you’ll be going home by boat at the end of next week.'”

"Well, the worst thing I ever did to anyone in my life was to trade the orange strip on my bed for a blue strip on someone else’s bed. I never heard anything as a result of my devilry—and got home at least two weeks ahead of the poor SOB who took my place and went by boat!"

[THE END.]

[In Phil's written presentation, he never once mentioned his extraordinary racing career, the story about getting blood from a Luftwaffe pilot, his ‘uneventful’ (as he described it to me) inland landing on D-Day +1, or his seven (7) Bronze Stars, Purple Heart, Air Medal, POW Medal, and Campaign Medals. Perhaps he was just sticking to what he was asked to speak about to the Citrus Aviation Association or perhaps it was a reflection of his self-effacing modesty--or both.]

"About the time of Hitler’s death, our camp was liberated by the Russians (May 1, 1945), The guards had left, and the Russians came galloping in on horses, accompanied by an assortment of vehicles, including jeeps. They asked how they could help us. We said, “Food. We’re all starving.” Next thing you know, the Russians are herding liberated chickens and pigs into the camp. Man, did we all get sick.

"I won’t go any further about the POW camp as I’m sure a number of movies have covered it well."

GOING HOME

"The day after Germany’s unconditional surrender was signed (May 7, 1945), a number of B-17’s landed at an adjacent field where there had been a factory that produced the German jets—the first to provide them. In conjunction with the plant there was one runway I estimated to be at least 6,000 feet long. ["Operation Revival: Rescue from Stalag Luft 1."]

"Since I was listed as an ambulatory patient with a pulmonary problem, I went out on one of the first B-17’s along with a few from the Camp Hospital. We wound up in a large hospital near Paris where they gave us a physical and any needed treatment. And, they scheduled our trip back to the states.

"While in the hospital, I noticed at the foot of each POW’s bed a large envelope containing his records. There also was a 12-inch by one inch strip of either blue or orange paper. I asked the nurse what the color stripes were for and she said: 'If it’s blue, you are going home by air the day after tomorrow. And if it’s orange, you’ll be going home by boat at the end of next week.'”

"Well, the worst thing I ever did to anyone in my life was to trade the orange strip on my bed for a blue strip on someone else’s bed. I never heard anything as a result of my devilry—and got home at least two weeks ahead of the poor SOB who took my place and went by boat!"

[THE END.]

[In Phil's written presentation, he never once mentioned his extraordinary racing career, the story about getting blood from a Luftwaffe pilot, his ‘uneventful’ (as he described it to me) inland landing on D-Day +1, or his seven (7) Bronze Stars, Purple Heart, Air Medal, POW Medal, and Campaign Medals. Perhaps he was just sticking to what he was asked to speak about to the Citrus Aviation Association or perhaps it was a reflection of his self-effacing modesty--or both.]

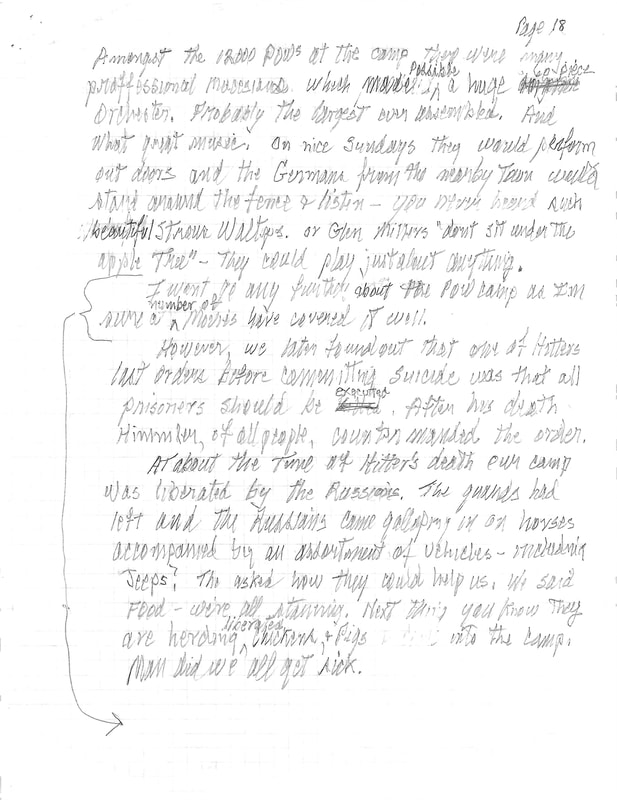

ADDENDUM 1. Sample pages of Phil’s handwritten presentation to the Citrus Aviation Association. (See expanded version.)

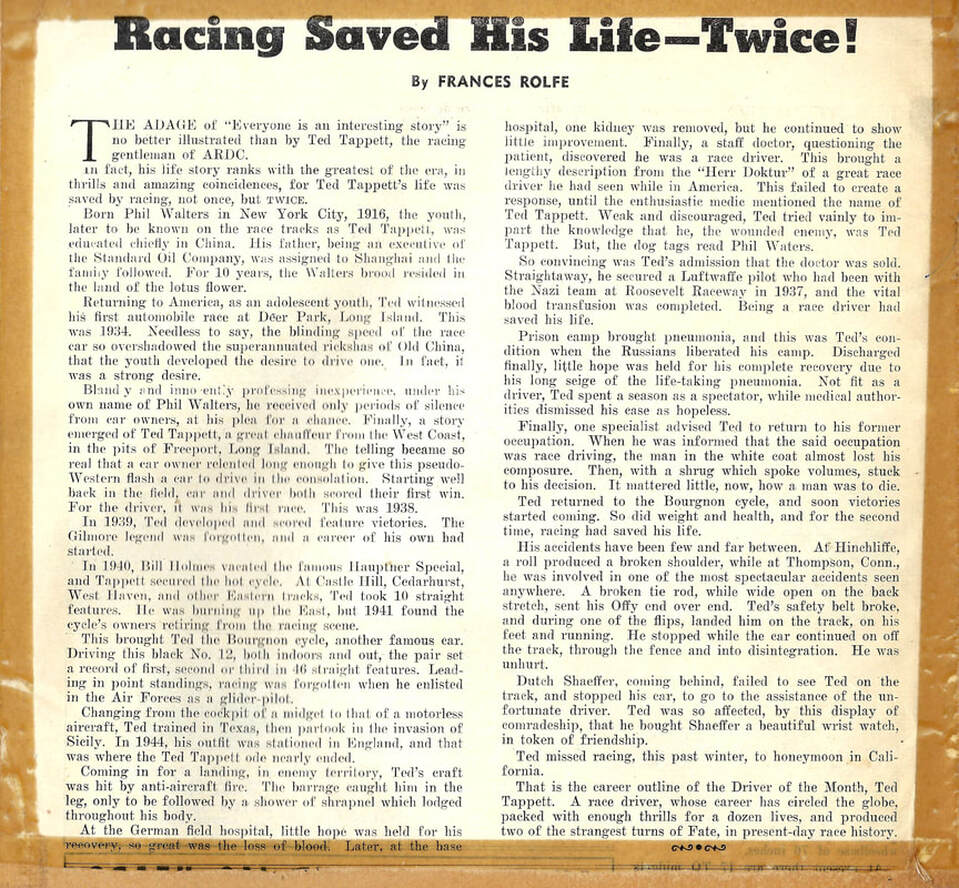

ADDENDUM 2. After the war, and soon after Phil started racing again, this article (circa 1947) appeared in National Speed Age Magazine which named him "Driver of the Month." It includes a more detailed account (though slightly different) of Phil's experience in the German hospital and a recounting of "one of the most spectacular accidents seen anywhere" in which Phil was thrown from his car.

Addendum 3. Some of the medals earned by Phil Walters